What Are Two Reasons That Less Babies Were Being Born in Europe During the Late 19th Century?

The birth rate in the EU decreased at a slower pace between 2000 and 2019 than before

In 2019, 4.167 million children were born in the EU, corresponding to a crude birth rate (the number of live births per 1 000 persons) of 9.3. For comparison, the EU crude birth rate was 10.5 in 2000, 12.8 in 1985 and 16.4 in 1970.

During the period 1961–2019, the highest annual total for the number of live births in the EU was recorded in 1964, at 6.797 million. From this relative high up to the beginning of the 21st century, the number of live births in the EU declined at a relatively steady pace, reaching a low of 4.365 million in 2002 (see Figure 1). This was followed by a modest rebound in the number of live births, with a high of 4.675 million children born in the EU in 2008, in turn followed by further annual reductions up to 2019 (4.167 million live births).

Figure 1: Number of live births, EU, 1961–2019 (million)

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind)

1.53 live births per woman in the EU in 2019

In recent decades, Europeans have generally been having fewer children, and this pattern partly explains the slowdown in the EU's population growth (see Population and population change statistics). The most widely used indicator of fertility is the total fertility rate: this is the mean number of children that would be born alive to a woman during her lifetime if she were to pass through her childbearing years conforming to the age-specific fertility rates of a given year. A total fertility rate of around 2.1 live births per woman is considered to be the replacement level in developed countries: in other words, the average number of live births per woman required to keep the population size constant in the absence of migration. A total fertility rate below 1.3 live births per woman is often referred to as 'lowest-low fertility'. The total fertility rate is comparable across countries since it takes into account changes in the size and structure of the population.

In 2019, the total fertility rate in the EU was 1.53 live births per woman (as compared to 1.54 in 2018 - Figure 2). The EU's total fertility rate rose from a low of 1.43 in 2001 and 2002 to a relative high of 1.57 in 2010, subsequently followed by a slight decrease to 1.51 in 2013 before a modest rebound up to 2017.

Figure 2: Total fertility rate, EU, 2001–2019

Source: Eurostat (demo_find)

Figure 3 shows that the mean age of women at childbirth continued to rise between 2001 and 2019, from an average of 29.0 to 30.9 years. One partial explanation for the increase in the total fertility rate is that it may have been related to a catching-up process: following the trend to give birth later in life (witnessed by the increase in the mean age of women at childbirth), the total fertility rate might have declined first, before a subsequent recovery. An increase in the mean age of women at birth of first child can also be observed, from a value of 28.8 in the EU in 2013 to a value of 29.4 in 2019.

Figure 3: Mean age of women at childbirth and at birth of first child, EU, 2001–2019

Source: Eurostat (demo_find)

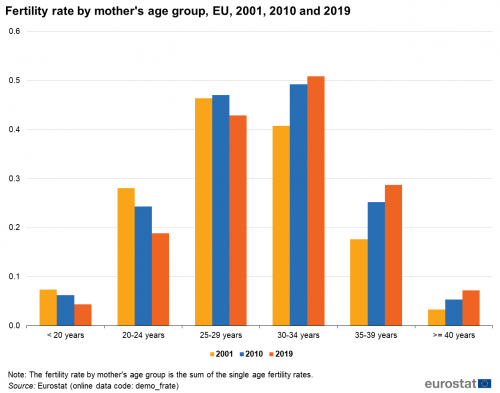

Indeed, women in the EU appear to be having fewer children while they are young, and more children later. Figure 4 shows the growing relevance of fertility at ages higher than 30 in the EU. While the fertility rates of women aged less than 30 in the EU have declined since 2001, those of women aged 30 and over have risen. In 2001, the fertility rate of women aged 25-29 years old was highest among all the age groups. In 2019, the fertility rate of women aged 30-34 became the highest. The fertility rate at ages higher than 35 is also rising.

Figure 4: Fertility rate by mother's age group, EU, 2001, 2010 and 2019

Source: Eurostat (demo_frate)

Among the EU Member States, France reported the highest total fertility rate in 2019, with 1.86 live births per woman, followed by Romania, with 1.77 live births per woman and Ireland, Sweden and Czechia all with 1.71 live births per woman. By contrast, the lowest total fertility rates in 2019 were recorded in Malta (1.14 live births per woman), Spain (1.23 live births per woman), Italy (1.27 live births per woman), Cyprus (1.33 live births per woman), Greece and Luxembourg (both 1.34). In most of the EU Member States, the total fertility rate declined considerably between 1980 and 2000–2003: by 2000, values had fallen below 1.30 in Bulgaria, Czechia, Greece, Spain, Italy, Latvia, Slovenia and Slovakia. After reaching a low point between 2000 and 2003, the total fertility rate increased in many Member States and by 2019, all of them except Malta, Spain and Italy reported total fertility rates that were above 1.30 (Table 1).

In the past 45 years, total fertility rates in the EU Member States have, in general, been converging: in 1970, the disparity between the highest rates (recorded in Ireland) and the lowest rates (recorded in Finland) was around 2.0 live births per woman. By 1990 this difference — between a high in Cyprus and a low in Italy — had decreased to 1.1 live births per woman. By 2010, the difference had fallen again to 0.8 live births per woman with a high in Ireland and a low in Hungary. By 2019 the difference narrowed to 0.7 when the highest total fertility rate was recorded again in France and the lowest rate was recorded in Malta.

Table 1: Total fertility rate, 1960–2019 (live births per woman)

Source: Eurostat (demo_find)

Total fertility rate and age of women at birth of first child

Figure 5 shows a plot of the total fertility rate against the mean age of women at the birth of their first child in 2019. Some of the countries with the highest total fertility rates also had a relatively high mean age of women at the birth of their first child. Four different groups of EU Member States can be broadly identified based on their position with respect to the EU averages (as identified by the quadrants defined by the blue lines). The first group (top right quadrant) is composed of Denmark, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway where both the total fertility rate and the mean age of women at the birth of their first child were above the EU average. A second group (bottom left quadrant) is made up of Croatia, Malta and Poland: both their total fertility rates and mean ages of women at the birth of their first child were below the EU averages, as was also the case in North Macedonia and Serbia. A third group (bottom right quadrant) composed Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Austria and Portugal, as well as Switzerland recorded a higher than average mean age of women at the birth of their first child but a lower total fertility rate than the EU average. The final group (top left quadrant) was composed of Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia, as well as Iceland and Turkey; in each of these, the total fertility rate was higher than the EU average but the mean age of women at the birth of their first child was below the EU average. In Finland the mean age of women at the birth of their first child was the same as the EU average, while the total fertility rate was below the EU average.

Figure 5: Fertility indicators, 2019

Source: Eurostat (demo_find)

As can be seen in Map 1, 29.4 years was the mean age of women at birth of first child in the EU in 2019. The lowest mean age at birth of first child can be found in Bulgaria (26.3 years) and Romania (26.9 years); the highest values can be observed in Italy (31.3 years) and in Spain and Luxembourg (both 31.1 years).

Map 1: Mean age of women at birth of first child, 2019

Source: Eurostat (demo_find)

Almost one fifth of children born in the EU in 2019 were third born or subsequent children

Close to half (45.8 %) of the children born in the EU in 2019 were first born children, with this share exceeding half in Romania, Malta, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Bulgaria (see Figure 6). By contrast, the lowest shares of first born children were recorded in Ireland and Estonia (both with 38.8 %) and Latvia (39.0 %).

In the EU, more than one third (35.7 %) of all live births in 2019 were of second born children, around one eighth (12.6 %) were of third born children, and the remaining 5.9 % were of fourth born or subsequent children. Across the EU Member States, the highest share of the total number of live births ranked fourth or subsequent was recorded in Finland (10.3 %), followed by Ireland (9.0 %) and Belgium (8.1 %). Turkey also recorded a high share of live births ranked fourth or subsequent (12.7 %).

Figure 6: Share of live births by birth order, 2019

(%)

Source: Eurostat (demo_find)

More than 65 % of the children born in Luxembourg in 2019 were from foreign-born mothers (see Figure 7). In Cyprus, Austria and Belgium around one third of children were born in 2019 to foreign-born mothers and two thirds were born to native-born mothers. On the other hand, 98 % of live births in 2019 in Bulgaria, Slovakia and Poland were born to native-born mothers. Compared to 2013, most of the EU countries in 2019 showed an increase in live births from foreign-born mothers. Malta recorded the highest increase in live births from foreign-born mothers (19 p.p. from 11 % in 2013 to 30 % in 2019) followed by Greece (7 p.p. from 14 % to 21 %), Spain (6 p.p. from 22 % to 28 %) and Sweden (5 p.p. from 26 % in 2013 to 31 % in 2019) .

Figure 7: Share of live births from foreign-born and native-born mothers, 2019

(%)

Source: Eurostat (demo_facbc)

Data sources

Eurostat compiles information for a large range of demographic data, including statistics on the number of live births by sex (of new-borns), by the mother's age, citizenship, country of birth, level of educational attainment and marital status. Fertility statistics are also collected in relation to the number of births and by birth order (in other words, the rank of the child — first, second, third child and so on). A series of fertility indicators is produced from the information collected, including the total fertility rate and fertility rates according to the mother's age, the mean age of women at childbirth, the crude birth rate or the relative proportion of births outside of marriage.

Context

The EU's social policy does not include a specific strand for family issues. Policymaking in this area remains the exclusive responsibility of EU Member States, reflecting different family structures, historical developments, social attitudes and traditions from one Member State to another. Nevertheless, policymakers may well evaluate fertility statistics as a background for family policymaking. Furthermore, a number of common demographic themes are apparent across the whole of the EU, such as a reduction in the average number of children being born per woman and the increasing mean age of mothers at childbirth.

The EU has been going through a period of demographic and societal change. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic will leave a lasting impact on the way we live and work together. The outbreak came at a time when Europe had already been going through a period of profound demographic and societal change. More information of the work of the European Commission 2019-2024 to tackle the impact of demographic change in Europe can be found in the European Commission dedicated pages.

What Are Two Reasons That Less Babies Were Being Born in Europe During the Late 19th Century?

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Fertility_statistics

0 Response to "What Are Two Reasons That Less Babies Were Being Born in Europe During the Late 19th Century?"

Post a Comment